Open Doc Lab Project Manager Beyza Boyacioglu interviewed Alison S.M. Kobayashi about her project Say Something Bunny!. A collaboration between Kobayashi and Christopher Allen, this immersive documentary performance is based on a found audio recording from a 1950s’ New York family. The project unpacks a family history, the spirit of an era, and the affordances of a now-obsolete media technology–wire recorder–through archival research, textual analysis, reenactment, and speculation. It is a one-of-a-kind example of non-fiction storytelling that successfully combines a collective experience, live performance, and immersive media.

Beyza: Can you tell me a little about your artistic practice?

Alison: Since 2006, I have been making videos and performances that were based on found objects. Those would usually be looking through thrift stores, looking on the street, pretty much anywhere. Whenever I would stumble across something that had some sort of trace of the previous owner, I’d take it. I have this collection that I amassed over ten-eleven years. Usually these things would be very mundane in a lot of ways, something that a lot of us have, but don’t really think about how they have little traces of our identity, of our life on them.

I used to collect answering machine tapes. People donate their answering machines to thrift stores and they forget to take out the cassette tapes. So, I used to go to thrift stores and just buy the cassette tapes. You don’t really get to hear from the person that owns the answering machine, but you get the sense of their life from who’s calling, what they’re calling about. Like, “Pick up the kids,” or “You missed your appointment.” if they’re constantly late for things, you get a sense of a person’s personality…

So, that ended up becoming Dan Carter where I performed all the characters played on this answering machine. And it was similar in a way to Say Something Bunny!.

Since then, I have moved into doing some live performance starting in 2012. So, it really was a long trajectory of using found objects, making videos, doing performance for videos, then doing live performances, and then doing a combination of both found objects and live performance.

Beyza: What is the story behind Say Something Bunny!? How did it come into being?

Alison: I got it [the audio recording] in 2011. I was at UnionDocs. I was telling this musician who had just played a show there about how I worked with found audio recordings, and over the years different people have given me stuff, and he was like, “Oh, I have this thing and it’s on a wire recorder.” I said, “I’ve never heard of a wire recorder, send it to me if you can.”And he sent it to me. This recording was really special and I knew I wanted to do something with it. I wasn’t sure what at first.

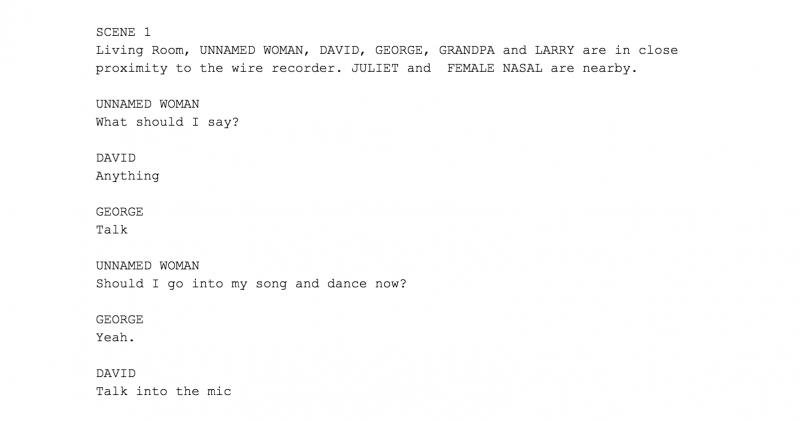

We [Christopher Allen and I] were like, should we make a video out of it? Should I try and recreate the era? And eventually I just had to get through this task of transcribing it between 2011 and 2015, and try and understand what they were saying.

Early transcription

Beyza: What is a wire recorder? What does it look like? How does it work?

Alison: It has a long history. I think that it began to be used at the beginning of the 20th century. It was used by soldiers as a recording device; it’s very heavy, but at that time, I think it was very portable, so they actually used it to record during World War I. Then records replaced it as the next recording device. And it had this second wind after World War II, where it was the first consumer recording device.

Wire recorder in action

So, the fact that this recording still exists is quite unique, because not a lot of people had a home audio recorder, and those who did, a lot of those recordings didn’t survive because it’s such a finicky machine and the wire itself is this material that’s not very forgiving to human error. The sound is recorded to a piece of steel that’s very thin and it’s magnetically recorded to it.

Wire reel

Beyza: And you started by decoding and transcribing the conversations from this found audio. Then what happened?

Alison: All of my previous work included putting myself in other people’s shoes and imagining who they were. But for the most part, it’s been a work of imagination or fiction; I never got to the point of researching people. But, in this piece, I thought it would be really helpful if I could try and find out, who these characters were and what I can learn from that.

And that’s when I found the 1940 census record that we shared in the show. It had all of the characters and I was like, now that I have this, this is just completely transformed the project. I can’t go back to not knowing this. So I was like, “Okay, I’m going to commit myself to researching this and looking into archives, trying to find out who these people are, what they ended up doing, what they did before the wire recorder.” All in an attempt to understand what they’re talking about and how they’re talking to each other in the wire recording. All the research is trying to point back to the conversations in the wires.

It’s strange how much, a lot of the characters were the same. How there’s so much in that tape of who they are, even though they might have been thirteen years old. People obviously grow but how you’re so much the same person when you’re thirteen, fifteen, seventeen.

Beyza: It is very difficult to describe the piece in a nutshell. How do you explain the format of the performance?

Alison: The performance is like, you listen to this audio recording together, assisted by a transcription of the audio recording, and throughout we take pauses where I share my insights, footnotes, interpretations, characterizations, discoveries, and revelations with the audience. I guess this would be the most simple way to describe it. But there is a lot of other things going on. It’s fiction and non-fiction. It’s using archives but also an active imagination. It’s not really in a singular category I think. We’re kind of trying to borrow things from different genres and in a way to create our own thing: Performance, documentary, theater piece, media art installation…

It’s a complicated thing. It’s not something that’s just an idea. You enter the room, you sit at the table and you kind of become a character even though you don’t have to perform or say anything. You’re there, and almost as an actor preparing for the role of being a character, without having to do anything.

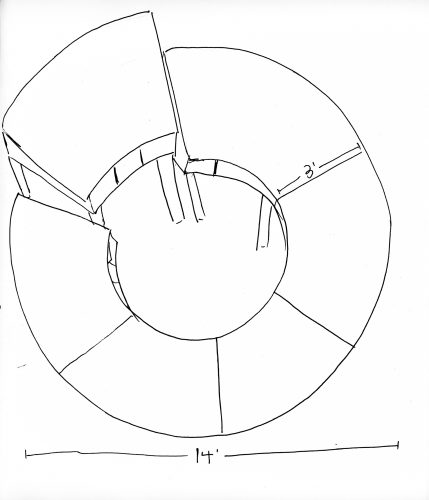

Rough table sketch

Alison S. M. Kobayashi in Say Something Bunny! photo credit Henry Chan

It’s not an existing format so there’s not much to compare it to. We [Christopher Allen and I] were talking about research discoveries and how I found out that David [one of the characters on the wire recording] was a playwright. He was lyricist who was involved with Broadway and wrote scripts. So this format of, a bunch of actors gathering in a room, coming together for a read-through was really something that was part of his biography and something that he had experienced many times in the seventies. We were really inspired by his history to create the format of the show.

Beyza: So who are the people on the recording?

Alison: It’s a Jewish and New York family who have been here for multiple generations. They’re Jewish but are somewhat secular at the time because of circumstances in the United States and pressure to assimilate. A lot of them grew up in New York City but the recording takes place in suburban Long Island. It’s this main family and their neighbors, the Tenanbaum family.

They are just like regular people in a lot of ways. They’re recording themselves because David has this novelty machine. I’m sure many of us do the same when you get an iPhone or something, for Christmas, and you are like, “Let’s test the new slow motion video function!” So it’s a very timeless moment where one person has this device and everyone kind of wants to see how it works. That moment is captured along with all the other stuff around it.

Beyza: From a documentary point of view, what does this archival audio tell us about the life in the 50s’ America?

Alison: I feel there’s something about it that’s very timeless. I feel very connected to it, when I look back at my family’s audio recordings from the 90s. They are very similar. How when someone is documenting something, you’re asking people to perform for you in this strange way. Unless you’re secretly documenting them—which also happens on the audio recording. It’s kind of this timeless moment of “I have the camera on you, do something!” And you’re like, “Okay! I’m doing this thing.” What have I seen on television? Oh I’ll do a commercial. So sound off for Chesterfield!

How pop culture always finds its way into home movies because we don’t know how to perform, so we look at what we see as performance. Television, hosts on television shows, hosts on the radio, what do they do? They say commercials. So that was really interesting to see how much, what was around them at the time, transposed onto this audio recording and became part of the content.

Beyza: It also reveals aspects of family dynamics and identity politics of the time.

Alison: I think that the post-war era was very interesting in terms of immigrant identity in the United States, which is just very subtly revealed in the recording. The 50s, it’s such an intense time, in terms of family traditions. How you see yourself in an American landscape, or for my family a Canadian identity landscape.

I think that a lot of people [from the audience] are like, “They’re Jewish, but why are they talking about Christmas and Easter so much? Shouldn’t they be talking about Hanukah and Passover?” I think it’s probably very similar to my dad’s family who are Japanese Canadians. They had been in Canada, like the family in the audio recording, for multiple generations. But after World War II they were like, “Let’s assimilate and become Canadian.” My grandfather’s name is Kiyomi, and my grandmother’s name is Shinako. They named their kids George, Alice, Margaret, Shirley, and Roy. Very Canadian, western names. In my opinion, for the people in the recording, it’s not so much about them becoming Christians, it’s more so them adopting American culture, which is Christmas and Easter, which are Christian holidays. But I think that they found their own way to celebrate that.

Beyza: I think gender roles of the time come up in interesting ways too.

Alison: There’s this moment where the conversation just completely divides into gender. Everyone is talking at the table, they’re all chatting about whatever, and then all of a sudden these two conversations break off, and the women talk about cooking and they talk about this meal that they had at their Aunt Benny’s house: “What did she cook? She made this roast beef that was rare. It was so amazing!” In the other conversation—only men are in it—they’re talking about smoking and how to keep your tobacco moist. It’s almost like this mini smoking room where men go off and have their masculine conversation, and then women go off and have their conversation about cooking and food.

Also in the second recording, certain characters, like Julian and Stella are not there as much. Probably because they’re cleaning up after people in the kitchen, or they’re in another room doing hosting tasks. And there’s this one moment where Shirley screams, “Oh the turkey!” She, as the woman, was supposed to be preparing the thanksgiving turkey, and because she wanted to participate in this wire recording and have her voice heard, she’d completely forgotten about this feminine task of cooking dinner for everyone.

Beyza: You imagine one of the young women characters, Bunny Tenenbaum, as a feminist, reading The Second Sex. How did you come up with that interpretation?

Alison: I thought that Bunny was such a fun character because she’s totally not interested in participating, and I really tried to get something out of her. She’s the first character to go off to college and she’s in school at the moment. They’re just trying to quiz her and taking on the role of probably a quiz show that they’ve seen on television. Like, “We’re going to interview Ms Bunny Tenenbaum right now!” and she’s like, “I don’t know if I want to perform.” She just seems like she’s a woman who knows what she wants to do, and knows what she doesn’t want to do. The Second Sex had come out around that time and I just really loved the idea that she’d be reading this piece of feminist literature. That was something that I projected onto that character. There’s nothing in my research that led me to think that she had read Second Sex, but it was just her personality and the way she interacted with the other people on the recording that I was like, “Why not?” It’s one interpretation, but whatever your interpretation of Bunny is, that is also correct.

Alison S. M. Kobayashi in Say Something Bunny! as Bunny reading “Second Sex” photo credit Henry Chan

Beyza: The performance is named after a line they keep saying to her: “Say something Bunny!” How did you choose that title?

Alison: Bunny was such a huge part of my research because she was the only character who was fully named. Because it’s a family recording—and I’m sure you have this when you’re with your family—no one calls each other by their last name or their full name. It’s always like, “Hey Allie,” “Hey kiddo,” or something. Everything’s kind of coded in family speak.

But because they do this formal interview with her, “Now we will speak to Ms Bunny Tenenbaum,” as a radio reporter, she’s the only character on the recording who is named. So she was such a big part of trying to track down who they were, and also her name is the most amazing name; “Bunny” is so 50s. Tenenbaum was very Jewish and kind of the combination of that was so wonderful. I just love her name, and I love her character.

Beyza: What was the clue that led you to the family’s census records?

Alison: It was Sam and Stell’s wedding anniversary and the Cornell/Penn football game; that was the connection. It was really just trying to figure out what day it [football game] was, then finding Sam and Stell’s anniversary, and through that, getting to find the census. Being able to know that it was the correct census was because Barbara Tenenbaum showed up on it. With this research there are always so many different options and any of them could be right, and you have to have these confirmation checks.

Beyza: What was your research method like?

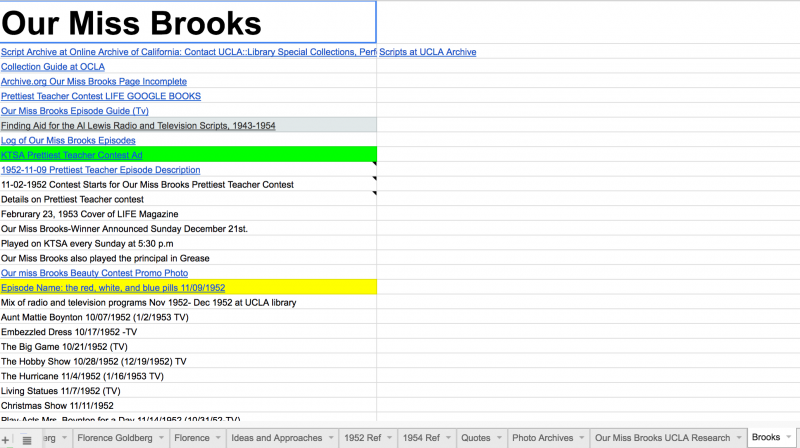

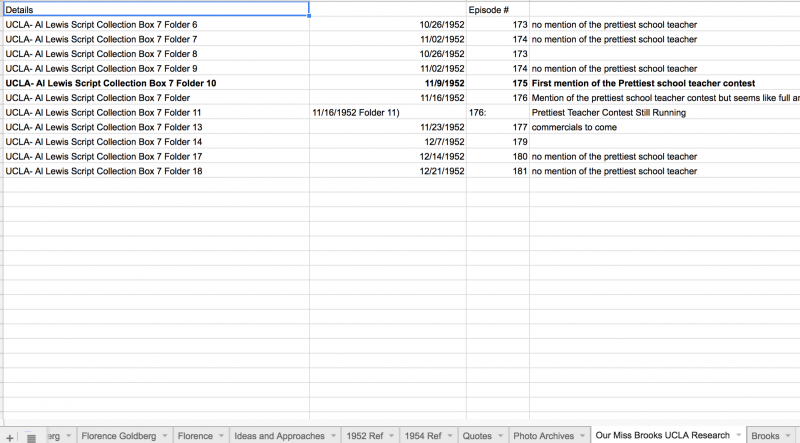

Alison: I am a complete amateur, so the research was really, at the beginning, just trying to find anything. I used whatever is available to the public as online searchable archives: ancestry.com, genealogy.com, newspapers.com. I would start accounts in free trials for a lot of websites like yearbook websites. I’d also go to public libraries. New York Public Library was really amazing.

Once I did it for longer, I realized I need to keep track of all of these things and I just kept a spreadsheet. Each character had a different sheet on the spreadsheet. So that just kept growing and growing and of course there were so many dead ends with this. You start following someone named David Newburg and you’re like, oh great I found him. And then some sort of hint comes up that says it’s the wrong person and I spent all this time learning all this stuff about this person. It’s always like, checking back to see what was right, what was wrong.

Our Miss Brooks Research

Beyza: Does anyone from the family know about “Say Something Bunny!”?

Alison: After we finished writing Say Something Bunny!, we went on a trek to try Larry [the youngest character]. It really was unclear if he was still living. I had seen the graves of all of the other characters with the exception of his, so always wondered. There was this chance that he was still out there. And we found him.

Beyza: How much of the story is fiction or speculation, versus fact, and how do you construct those imaginary stories?

Alison: Part of the story is also my journey as a researcher. So the story is not just the family’s biographies. It’s complicated. There are inserts [in the script book] that are illustrations I’ve made of George seeking a secretary. That is fiction. I tried to allow the audience to understand that that’s fiction, by hand drawing it instead of trying to perfectly recreate an ad for his business. So there are these hints that lets you know that it is an interpretation.

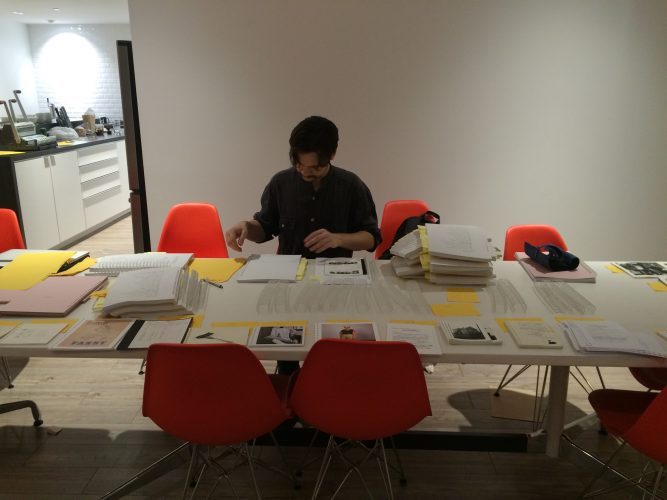

Process and asset creation

[During the performance] I would say, “This is an interpretation. It could be this, it could be this, it could be this. I’m not sure, but let’s try it this way.” Funny things like reading The Second Sex. But most of my narratives were based on some sort of hint in the document. Usually I wouldn’t make something up out of left field.

Beyza: The technology behind the performance is fascinating. The audience sits around a custom-made round table and you perform in the hollow middle part of this table, or around the audience. You have tiny screens in front of each audience member, automated lights, and an immersive projection; you sometimes use a live feed camera to project your performance on the wall… Can you talk about the design process and how all these components are choreographed and automated?

Alison: This is definitely Christopher’s forte. Christopher and I wrote the script together but he was also the person behind the technical side of the project. He really did a lot of that technical design, the lights, the microphone… There is also surround sound so the audio comes out of all the speakers, which are built-in to the table, and then at moments when we play back the audio, it comes out of a speaker associated with where that character would be sitting at the table.

Alison S. M. Kobayashi in Say Something Bunny! photo credit Henry Chan

Alison S. M. Kobayashi in Say Something Bunny! photo credit Henry Chan

There’s a lot of different details that he was able to create to make this come alive. I feel like the technical setup is what really makes the performance more magical, its something that you could try and perform as a lecture potentially, but because of the technical apparatus of the performance and the table and the projection and the lights, it immerses you in it. And then you are like, “Oh it’s happening around me. I hear it, it’s close to me. It feels very immediate.”

Technical test of system at UnionDocs

Christopher is coming from running UnionDocs and he has a background in experimental theater. He very quickly learned how to use this program, QLab, which is the queuing software that allows you to do projection, lights. It was in a combination with a lighting software and QLab that he was able to make all of these components play out quite seamlessly, which is quite a technical feat for a performance. Also, based on my cues, he has about 2,000 plus cues that have one media thing connect to another, either turning a light on or off, playing a video or an audio clip throughout the performance.

I was also working with designers from Toronto. The reading table was designed with Michał Dudek and built by Michał Dudek and Richard Perri; script designed with Bartosz Gawdzik.

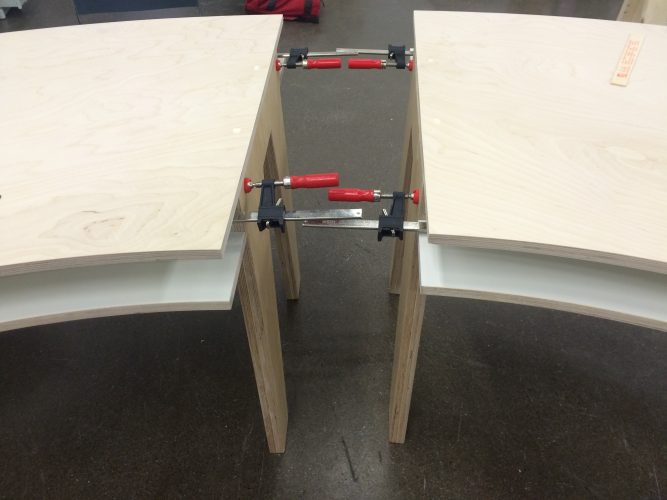

CNC cut table

Table construction at Gallery TPW

Beyza: How do you describe this piece? What genre or field of artistic practice does it belong to?

Alison: We’ve been saying immersive performance because I think it really tries to bring in the audience in this bizarre participatory spectatorship that’s very unique to this piece specifically.

Beyza: What was your inspiration when you were designing this project?

Alison: A lot of it was very much inspired by books. Because we were also making a book work for the first time, in terms of making that script.

Book design and construction

Audience-participants are following the audio on their scripts in Say Something Bunny! – photo credit Henry Chan

I really loved this book by Leanne Shapton called Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry. It is basically an auction catalog of this couple, and going through all of the items that represent their relationship and it leads to their breakup. It tells a story of a relationship and a breakup through their objects. And I really love Sophie Calle’s books.

Beyza: I think the script worked really well in terms of grounding the audience and focusing them on something tangible, while immersing them in a bunch of digital media and performance. And I’m glad you tell the audience from the start that they won’t have to read the text out loud. There is a moment of panic when you see the book in front of you!

Alison: There is a moment there where people are like “Oh no! I have to read this!”

Beyza: I think there is a lot of parallels between Living Los Sures Project of UnionDocs where Christopher is Founder/Executive Artistic Director and you are Special Projects Director. Living Los Sures takes a film from 1984 (Los Sures) and unpacks and annotates it in a very creative and collaborative way. Similarly, Say Something Bunny! uses a found audio recording as the framework for artistic research and the structure of the performance itself. Do you want to say a few words about this?

Alison: Before UnionDocs, I had not engaged deeply in documentary. Being a part of UnionDocs completely transformed, not only how I looked at documentary, but also how I looked at my own work. It was like “Oh, documentary doesn’t have to be just this one thing!” That it can be very playful and imaginative and much more experimental.

My work at UnionDocs has been very influential on this piece. How do you engage with archives in a way that feels very alive or bringing it to life again? And that these things aren’t just this thing from the past but it can have a life in the present. Los Sures is this documentary that is so deeply meaningful to so many people who lived in the neighborhood. I don’t know if [Say Something Bunny!] functions in that same way because it’s such a specific family, but also the story of that family does relate to a lot of people.

0 comments