by Sue Ding

Cook County Jail is the largest single-site jail in the United States, occupying 96 acres of land—more than eight city blocks—next to Chicago’s Little Village neighborhood. It admits approximately 100,000 pre-trial detainees each year, with an average daily population of 9,000; more than half of these inmates come from the residential areas surrounding the facility.1 The jail’s 25-foot-tall northern wall directly faces a row of single-family homes, presenting them with a view of gray stucco and concrete, chain-link fence, and barbed wire. Weeds poke up under windblown debris; there are no trees or sidewalks along the 800-foot-long wall. Little Village, or “La Villita,” is one of the country’s largest Mexican communities, as well as a vibrant commercial area. Yet the Cook County Jail looms over residents both physically and psychologically, an oppressive reminder of injustice, state violence, and for some, their separation from loved ones who are incarcerated inside.

Chicago-based artist and Little Village native Maria Gaspar grew up a few blocks away from the jail, and visited it as part of a “scared straight” elementary school field trip; she vividly recalls seeing the men in their cells, and the unspoken message that “you didn’t want to end up there.” In 2012, she began the 96 Acres Project: “a series of community-engaged, site-responsive art projects that address the impact of the Cook County Jail on Chicago’s West Side.” 96 Acres’ artworks and events gather together artists, educators, activists, formerly and currently incarcerated people, youth, and jail administrators in conversations about space, power, change, and community.

Space and Power

All spatial narratives are also structures of power. The 96 Acres Project shows how participatory location-based media can reveal, interrogate, and contest these structures. Speaking about the Cook County Jail, Maria Gaspar says, “The space is both visible and invisible. And that to me really signifies this larger understanding about our carceral system—either you see it or you don’t. Maybe you can afford not to see it, but we’re all affected.”

The project is part of an expansive tradition of embodied interventions taking place at sites of contestation—of sit-ins, marches, and other demonstrations—as well as a long history of public art and social practice art. The project itself has taken many forms, including zine-making workshops, an oral history archive, videos projected on the jail wall, and gallery exhibits. Here, I focus on its use of digital technologies to amplify community-based practices and create compelling spatial narratives. 96 Acres and the Cook County Jail also offer a constructive lens through which to interrogate how power is intertwined with spatial narratives, and how creators and communities can utilize participatory location-based approaches to reclaim and reimagine existing narratives of public space.

One of our most fundamental notions of freedom, understood at a bodily level, is freedom of movement: the ability to move around in space according to our needs and desires. Conversely, spatial power—the power to allow or refuse physical access to space, to define space, to surveil space—is a key component of systems of control and subjugation. Spatial power structures are simultaneously visible and invisible; Henri Lefebvre writes that by examining spatial arrangements, we can see how these structures perpetuate justice and injustice.2 In “Spatial Justice: A Frame For Reclaiming Our Rights To Be, Thrive, Express And Connect,” the Boston-based Design Studio for Social Intervention succinctly traces the global and historical use of spatial power:

Practices of domination, subjugation, and resource depletion have been historically honed and brought to bear through space. The taking of land, the massive capturing of bodies and taking them from one space to another, environmental exploitation, forced movement through economic deprivation […] Most wars, conflicts and genocides have at their core spatial claims and have resulted in distinct spatial power and consequences.

On a more local level, America has a profound and particular relationship to space—the frontier myth of freedom, rugged individualism, progress, and bootstrapping enterprise is perhaps our most defining national narrative, tying together Manifest Destiny, the road trip, the Space Race, and Silicon Valley. Consequently, the exercise of spatial power in the U.S. is particularly massive, contested, and freighted with symbolic significance. Our national history is full of mass relocations (voluntary and involuntary), indigenous land redefined as capitalist property, and marginalized populations further ghettoized.

American expansionism has run parallel to systematic racial and ethnic segregation as a way of defining and delimiting space. In Headmap Manifesto, a meditation on the disruptive potential of locative technology, Ben Russell describes American history as a spatial narrative of colonizing forces using technology to carve up the land into profit-generating, geographically bounded plots. He mentions railroads, ploughs, guns, windmills, and barbed wire—we can easily add more examples like redlining, urban renewal, or even the dominance of cars at the expense of more multi-use pedestrian spaces. Russell wonders, “The question of land refuses to go away. How can we separate the concept of space from the mechanisms of control?”3

Spatial Justice

In fact, while space is intimately connected with coercion and subjugation, space is also fundamentally linked to civic action—from the oft-cited Greek agora to Occupy Wall Street, from Tiananmen to Tahrir. Protesters claim the right to public discourse at the same time as they claim the right to public space, and the symbolism of the latter often undergirds the fight for the former. Marginalized communities have also long utilized practices like sit-ins, graffiti, and urban gardens to claim space, make their voices heard outside marginalized spaces, and redefine spaces on their own terms. For some activists and scholars, spatial modes of control are best understood—and best resisted—through the lens of “spatial justice,” which approaches space from a social justice lens, and vice versa. The Design Studio for Social Intervention understands the two as inextricably linked:

Spatial injustices end up embedded in both physical and social infrastructures that are shaped through decades […] If we demand the reworking of spatial arrangements, we are demanding the reworking of all other arrangements—those of nation, ownership, class, race, gender, etc.

They propose a spatial justice framework consisting of spatial claims, spatial power, and spatial links: the right to occupy and be safe in space, the right to succeed and express oneself in space, and the right to access and connect to essential resources and infrastructures. Geographer and urbanist Edward Soja situates spatial justice within a larger “spatial turn,” a growing emphasis on critical spatial perspectives across many different academic disciplines, as well as in public and political discourse.4 He writes, “Space is not an empty void. It is always filled with politics, ideology, and other forces shaping our lives and challenging us to engage in struggles over geography.”

Location-based Media and Contested Public Space

It is crucial to reflect on notions of spatial justice and public space when creating, consuming, and critiquing location-based works. Documentary filmmakers have long wrestled with issues of representation, exploitation, consent, and access; these issues are perhaps even more viscerally present in location-based media, manifesting in the safety of bodies in space. Ethical issues are physically felt, and the fundamental right to occupy space is at stake. When considering location-based works, we must ask ourselves questions like: Whose version of public space is being disseminated? Is a project contributing to processes of spatial injustice—for example, gentrification? Who is being invited into a space, and who participated in the decision to invite them? What are the power dynamics at play? Who is being made vulnerable?

Location-based media have sometimes served as vehicles for perpetuating spatial injustices. Many location-based projects present a homogenized and idealized version of public space, inherently excluding marginalized groups whose experiences—and very existence—complicate this narrative. This is frequently demonstrated in tourism apps commissioned by heritage and civic organizations, which highlight historic buildings and ignore more fraught histories. One community’s claim to space is also often prioritized over that of another group.

This exclusion and erasure are not necessarily intentional: all location-based media support a particular interpretation of public space, and a particular understanding—and hierarchy—of the stakeholders in that space. Understanding how location-based media intervene in the contested terrain of public space is essential in order to address ethical issues like exploitation and consent. However, negotiating multiple publics and competing interpretations of space is a complex and fraught process. A starting point is to imagine new uses of space, reexamine our assumptions about who belongs in certain spaces, and prioritize reaching people in ways that do not make them more vulnerable in space. Thinking through these lenses can highlight opportunities to create spatial narratives that draw on, and respond to, communities’ complex histories and meaningful relationships to space.

Community-based practices like oral history and collective storytelling can also help to reveal, document, and engage with these complex relationships to place. In many ways, community art projects that draw on locative and digital technologies are continuing these practices, and in doing so, they are not overlaying narratives, but rather revealing narratives that are already layered on the landscape. By engaging with these historical, communal, and personal narratives, and encouraging collaboration between diverse community stakeholders, participatory location-based media can intervene in public space in thought-provoking ways, build sustainable resources that address pressing needs, and create new connections among and between communities.

PARK

PARK was a 2015 participatory location-based project by artist Landon Brown and the 96 Acres Project: “A large-scale data visualization, public art, and radio broadcast event.” For one half mile of Sacramento Avenue, adjacent to the Cook County Jail, the organizers planned to fill all public street parking with crowd-sourced white, brown, and black automobiles, color-coded to represent the racial demographics of the jail’s inmate population (while Black people represent only 25% of Cook County’s population, they make up 67% of the jail’s inmates).5 At a specified time, all the cars were asked to tune into Vocalo 90.7, the local public radio station, for a live broadcast of B. B. King’s historic 1970 concert, “Live in Cook County Jail”—rolling down their windows to collectively “perform” the recording. Interspersed with the music, the broadcast featured community residents sharing personal anecdotes about the jail and neighborhood in real time. Vocalo 90.7 producers were onsite at several recording stations along the street, even interviewing the new Cook County Jail warden Nneka Jones Tapia. All the contributed stories joined 96 Acres’ ongoing archive of community media around the jail.

In some ways, the project was disappointing. Although Brown and 96 Acres hoped to include 100 cars (67 black, 19 brown and 14 white) in the project, their call for participation yielded less than half that number. And while Brown’s art practice is based around making data more accessible and bridging the gaps in understanding between citizens and policymakers, we can certainly question the efficacy and ethics of representing prison statistics—and human bodies and histories—with cars. However, the broadcast aspect of the piece was effective on several levels. The re-performance of B. B. King’s 1970 concert underscored the lack of progress in fighting mass incarceration in the years since, and underscored the historicity of the struggle. The cars along the length of the street playing the broadcast together resulted in a “quasi-stereophonic effect that permeated the space”6—viscerally and collectively creating a space for community discourse, and in doing so, imagining alternative uses of this oppressive space.

Cross-Community Collaboration and Co-Creation

PARK was perhaps most successful as an exemplar of cross-community collaboration and co-creation. These are key affordances of location-based media, which can bring together disparate groups for collaborative efforts rooted in physical proximity, community, and shared connection to place. PARK’s list of participating organizations included Vocalo 90.7, Yollocalli Arts Reach, Goodman Theatre, Imago Dei Violence Prevention Program, Project NIA, and the YMCA Youth Safety and Violence Prevention Program. The project received funding from four different organizations, including The National Endowment for the Arts and The Chicago Community Trust, and engaged “Public Official Stakeholders” including the Cook County Sheriff, two Cook County Commissioners, and the Cook County Board President. This plethora of partnerships and stakeholders is representative of 96 Acres’ approach: all project proposals undergo a “community-engaged review process via a community advisory committee [including] educators, activists, artists, violence preventions workers, community leaders, the formerly incarcerated, youth, and parents.”

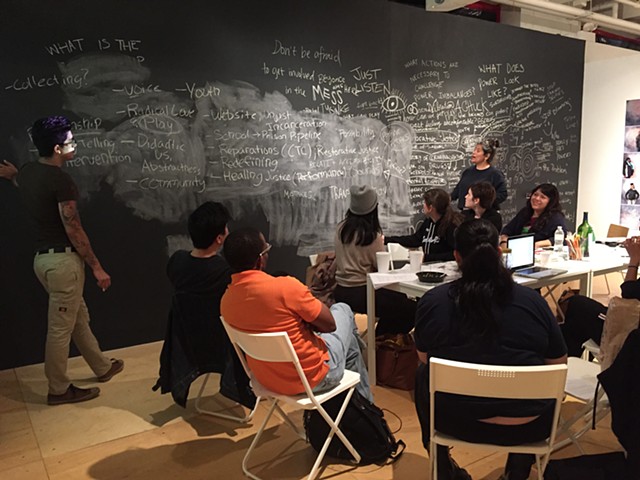

Social practice art in general tends to emphasize both collaboration within the community and community collaboration with outside entities—for example, design firms, local governments, or academic researchers. And social practice art itself draws on a rich history of place-based practice in marginalized communities, from street art to block parties. Co-creative approaches that put diverse stakeholders in collaboration with each other are crucial to fostering accountability, building solidarity, and generating productive discourse. For example, the 96 Acres committee deliberated at length about the role of public art in the community; some members prioritized beautification, pushing for a mural to cover the jail wall, while others saw that as a “band-aid” approach that failed to engage with deeper issues around incarceration and spatial power. The committee also debated whether certain projects were too abstract, or conversely, too didactic—and what exactly it meant for work to be “accessible” to the community. Collaborative approaches can also amplify people’s voices by bringing them into conversation with individuals and groups outside of marginalized spaces, and by developing new alliances. For example, 96 Acres was able to mediate between the Cook County Sheriff’s Office and the local community, as well as facilitate partnerships between artists and local nonprofit groups.

Collaborative community projects can be difficult to maintain over time, due to the vagaries of funding and the shifting priorities and availability of stakeholders. 96 Acres ran out of funding in 2016 and was forced to go on hiatus, although new funding has allowed Maria Gaspar to restart the project. She notes the importance of scaling activities appropriately for the capacity of a given project—something she learned after working on 96 Acres’ large-scale collaborations like PARK, which overtaxed the project’s small administrative staff. The project’s next phase will focus more selectively on art and audio workshops for people currently detained at Cook County Jail. Gaspar identifies the dynamic and ongoing nature of the project as a key component of both community-based and location-based work:

It’s not static images or static experiences. It’s organic, it’s evolving. That’s an important element of the work—we can evolve this issue over time and we can continue this dialogue through multiple projects. And it’s a project that I think needs constant reflection. Do we want to continue it? Is there another form it needs to take?

She is open to different potential futures for the project, and emphasizes that it exists alongside, and as part of, ongoing and longstanding community efforts for restorative justice. 96 Acres highlights how co-creative projects can address sustainability by taking on new forms and recognizing community stakeholders operating within different timeframes.

Reclaiming Spaces

As the spaces we inhabit become increasingly mapped, commodified, and surveilled, location-based media can function as a mode of resistance. Location-based approaches allow people to reclaim, redefine, and reimagine spaces by imbuing them with alternative narratives and meanings—or simply, as a starting point, by better understanding the ways that power operates through space. Many of 96 Acres’ community events focused on facilitating conversations about power and place—defined as physical, imagined, or internalized space. The project hosted several workshops around this theme, with content collaboratively shaped by artists, activists, and educators. The goal of engaging youth and educators in these events was to “radically imagine new narratives that allow us to actively participate in the transformation of our communities [and] to activate alliances, build solidarity, and continue working towards creating alternative and socially just spaces.”7 The workshop conversations were documented and used to create toolkits to facilitate further discourse among the community.

Location-based, co-creative approaches also allow communities to reclaim space in more tangible ways. For more than 20 years, residents who lived on Sacramento Avenue across from Cook County Jail were deprived of a simple but meaningful forum for community building and socialization—the block party. Although their front yards opened up onto it, the street was a restricted space, one that de-prioritized the community’s needs: because the street bordered the jail, residents were never able to obtain the necessary permits to block off the street for a party. Ninthe Serrano, a longtime resident of Sacramento Avenue, said, “Block parties were a big thing [for me, growing up]. Every kid looked forward to it all summer, and they’ve never had one here.”8 96 Acres’ PARK finally helped make this possible, albeit temporarily: the street was blocked off, children played with water balloons, and residents shared tables of food and snacks. By shaping an artistic intervention centered around occupying the street in front of the jail, and amplifying residents’ voices and needs through institutional collaboration between community arts nonprofits and the jail administration itself, 96 Acres redefined the space as one that served the needs of the community, rather than the criminal justice system.

While marginalized communities have a rich tradition of location-based tactics that are low-tech—from hand-drawn posters to neighborhood meetings to alternative tours—digital location-based media present powerful new opportunities for reclaiming space. Individuals and groups may not have the power to reorganize the city grid or tear down an oppressive building. But with the rise of location-based technologies, ubiquitous computing, and mobile media, Ben Russell argues: “New forms of collective, network organised dissent are emerging. Collectively constructive rather than oppositional. Now capable of augmenting, reorganising, and colonising real spaces without altering what is already there […].”9 With digital media, he notes, new meanings and narratives can be overlaid on existing ones without having to obtain authorization or undertake the risk and cost of physically changing spaces.

Stories from the Inside/Outside

All of 96 Acres’ projects have been sanctioned by the Sheriff’s Office—Maria Gaspar says this is essential to preserving long-term relationships between residents and local institutions including the jail and nonprofits, ensuring the sustainability of the project, and protecting youth participants. She sees 96 Acres as an ongoing community discourse, rather than fundamentally oppositional. In the project Stories from the Inside/Outside, 96 Acres projected several video animations on the jail wall, giving voice to people’s concerns about, and experiences of, the effects of incarceration on individuals, families, and the community. Narrated by Melissa Garcia, “Letters Home” explored her relationship with her father, through the lens of his letters home during his ten-year incarceration. “Freedom/Time” was a collaboration between artists Damon Locks and Rob Shaw, and eleven men incarcerated at Stateville Correctional Center. Stories from the Inside/Outside also featured writing by local youth.

Digital media offer alternative approaches to publicly claiming space when certain modes of mass communication and occupying space are unavailable or forbidden. Of course, locative technologies are also frequently inaccessible to marginalized communities, and furthermore, can easily act as avenues for surveillance. It is important to recognize both the communicative and subversive potentials of these technologies, as well as the necessity of continually interrogating and resisting the inequalities and subjugation they often perpetuate.

Conclusion

We are accustomed to ever-more pervasive and restrictive regimes of spatial control in our everyday lives: surveillance of our movements in space via cameras and mobile devices, constraints on the right to protest and record in public spaces, increasing border security apparatuses, and more generally, states and corporations decreeing where we can and cannot be, and when we can or cannot (or must or must not) be there. We are inculcated in these regimes; the spatial and temporal organization of many of our educational institutions mirrors that of prisons. It is easy for location-based media projects to perpetuate spatial modes of control, as they often rely on technology, infrastructure, and platforms that are inherently tied to industry imperatives, government regulation, and hegemonic notions of public space.

At the same time, it is possible to use new technologies and existing physical structures in ways that subvert or redirect their intended purposes. While spatial control and spatial injustice are ubiquitous, participatory forms of location-based media can challenge spatial boundaries, dispute conventional narratives of public space, and imagine transformative new uses of space. The 96 Acres Project highlights how this can be accomplished through cross-community collaboration and creative approaches to reclaiming space. 96 Acres is also part of a rich tradition of place-based practice in marginalized communities, and a long history of participatory location-based media that contest official narratives of public space. Walls—concrete symbols of state-imposed demarcations of space and restrictions of physical movement—have long been sites of heterogeneous collective discourse about public space, spatial power, and community. We need only look to the Berlin Wall for another example of an oppressive wall whose narrative of state power, separation, and deprivation was forever transformed by the contributions of artists, tourists, and everyday citizens.

Notes:

1. 96 Acres Project, “Cook County Jail.”

2. Henri Lefebvre, “The Right to the City,” in The Blackwell City Reader, ed. Gary Bridge and Sophie Watson (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2002).

3. Ben Russell, “Headmap Manifesto,” 1999.

4. Edward W. Soja, Seeking Spatial Justice (Minneapolis, MN: University Of Minnesota Press, 2010), 13-4.

5. Erica Demarest, “96 Acres, 40 Cars, 1,000s of Stories: Residents Reflect on Cook County Jail,” DNAinfo, August 16, 2015.

6. Sarah Rose Sharp, “On a Block in Chicago, a Participatory Project Visualizes Jail Data,” Hyperallergic, August 17, 2015.

7. Silvia Gonzalez, “Educational Zine Toolkits for Addressing Power,” accessed February 6, 2017.

8. Demarest, “96 Acres, 40 Cars, 1,000s of Stories.”

9. Russell, “Headmap Manifesto.”

Additional References:

Maria Gaspar, interviewed by author, 2017.

0 comments