by Deniz Tortum

Assent is a 10 minute interactive experience for Oculus Rift created by multimedia artist Oscar Raby that approaches the memory of Raby’s father, who, as a younger man, witnessed a mass execution in the early days of Pinochet’s regime in Chile. Haunted by this violence, Raby has struggled with how to remember and to understand this memory passed down to him by his father. A virtual representation of Raby, body dissolving occasionally into polygons, invites me to accompany him to relive the space of this traumatic memory. Assent begins in a model of Oscar Raby’s studio. Wearing the Oculus Rift is still a new experience for me, and it takes a few minutes to adjust to being able to control my gaze, to look anywhere I wanted in the space. I can move only by controlling where I look, by sustaining my gaze on particular locations or objects. As I follow Raby into a reproduction of the place where his father witnessed this execution, I see that each figure in the experience– executioners, victims, narrator– is modeled using the artist’ own body.

PUTTING ASSENT IN CONTEXT

Historical background

In 1973, a military coup overthrows the Allende administration in Chile. The culmination of political polarization exacerbated by the Cold War conditions, the coup leads to a military government under Augusto Pinochet lasting until 1990. The first years of the military regime are marked by massive human rights violations such as political killings, forced disappearances and torture. The junta’s approach is especially brutal in the first months. In the month following the coup, an army death squad known as the Caravan of Death travels by helicopter from city to city, carrying out mass executions of political prisoners. On October 16, 1973, the squad executes fifteen people who were being held at the La Serena jail, at the Arica Regiment in that city. Oscar Raby’s father, then a young military officer in that regiment, witnesses this mass execution. He has carried the traumatic memory with him ever since.

As the Pinochet regime ends in 1990, the new Aylwin administration promises “justice to the extent possible” and a truth commission is formed to reveal the human rights violations during the military government. Raby’s father knows that his witnessing of the execution would have further consequences. Because he was a soldier when he witnessed the execution, he was a witness in uniform. For many people in post-traumatic and polarized Chile, a witness in uniform equates to a perpetrator. Around this period, he decides to recount his story to his son. Oscar was sixteen when he first heard this story.

***

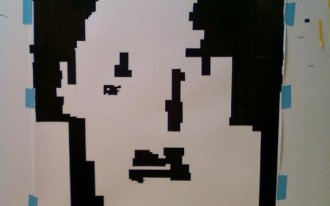

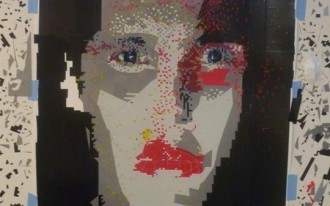

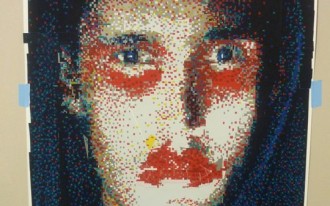

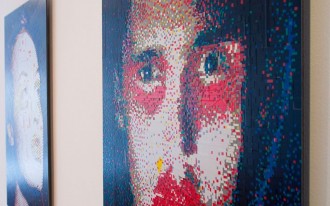

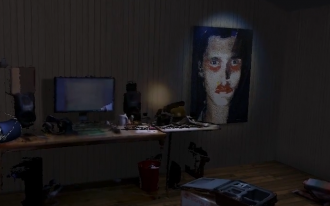

Assent opens in a virtual reproduction of Oscar Raby’s own studio. Walls are filled with his work from his last exhibition called Stick to Something (for long enough). The works in the exhibition are physical recreations of haunting digital images, created by meticulous work through treating sticky tape as pixels.

In Assent, Raby converts these physical works back into digital once again, processing their material from virtual to real to virtual.

Similar to how he sticks to these ghostly images for long enough and processes them multiple times, Raby also sticks to his father’s story. He carries it with him for almost twenty years. It is a story which bears an immense historical and emotional burden and which does not easily reveal the right way to be told. It required almost twenty years of active and passive contemplation for Raby to find the delicate tone and the right medium to meaningfully tell this story, making Assent the culmination of years of long intellectual and artistic inquiry.

Artistic background

Oscar Raby’s interdisciplinary art career and academic past play a substantial role in Assent’s strength. Raby does not treat the VR medium as a completely new technology, but rather as a new space for the fusion of many existing media and disciplines.

Raby studied architecture for three years before turning to multimedia design. After college, he founded the artistic collective O-inc and practiced performance art, doing physical performances and interventions in public spaces. One of his performances, Yo Y You, bears a great resemblance to Assent. For the performance, he invited artists from different fields to have boxing fights. As two artists fought on the ring, other artists captured the fight in their practiced medium, be it illustration, painting or photography. Raby also put a large canvas on the ring and paint under the fighters’ feet, causing them to leave colored footsteps on the canvas as they fought. By capturing the different interpretations of observers and the bodily traces of the performers at the same time, the piece explores how memory and history reconstruct violence and conflict.

Raby then returned to screen based media, working on video art and multimedia installations. Before moving to Melbourne, he worked on a massive installation project in Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Santiago. He worked silently on this project, which draws attention to human rights violations committed during the military regime. He did not tell anyone that his father had been a witness in uniform. After a year of hard work when everything was almost ready to go, an earthquake of 8.8 magnitude hit Chile, leaving the installation (the screens, speakers, frames) shattered and in ruins.

He left documentation for the installation’s reconstruction and moved to Melbourne before seeing the opening of the museum. For him, this marks a very poetic turn of events; even with his best effort, he was not able to fix history.

In Melbourne, Raby found a chance to reflect upon himself and began constructing a piece about his father’s story through his own memories. During this period Oculus headset became available for developers. Raby realized that VR could be the perfect medium to breach the gap between his two distinct practices, body based practice and screen-based media. As he developed Assent he informed the piece with his background in performance art, video art, architecture and theater design.

PROCESS

Technologies & Techniques:

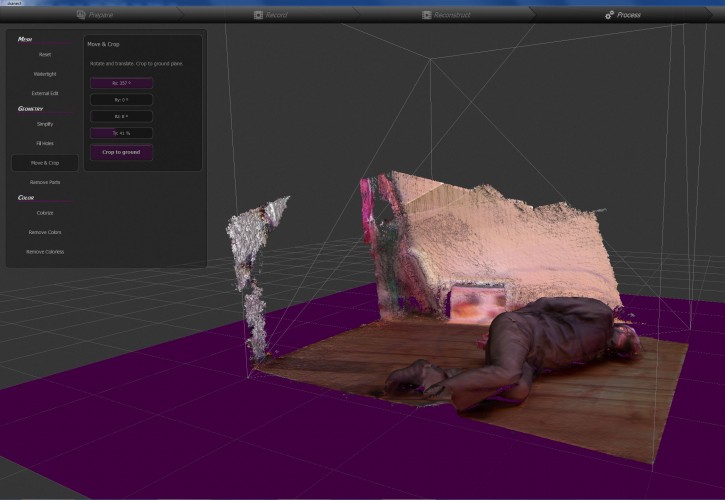

3d Scanning

In Assent, all the characters are 3d scanned models of Oscar Raby posing in different clothes and positions. To create the models, Raby uses a Kinect sensor and Skanect software. This technique is similar to how video game characters are captured. The sensor shoots a ray of infrared beams which become distorted when they land on a body. Through these distortions, the volume is computed by the processor. Skanect gathers all this information and turns them into a mesh. The other camera on Kinect gathers the color information and completes the model. For his first scan, Raby attaches a Kinect and a lamp to a tripod and revolves in front of the sensor by himself.

One of the early 3d scans contains glitches, where half of Raby’s body is missing. However, this imperfect artifact marks the beginning of the project and reveal the peculiarities of the medium, and Raby decides to keep this broken figure in the final piece.

Later on, Raby enlists his wife’s help in scanning. A full body scan would usually take a minute or two, during which Raby needs to remain completely still. Raby notes that aspects of this process are very similar to early photography when the photographer goes under a hood for two minutes, and the subjects need to be still for that duration.

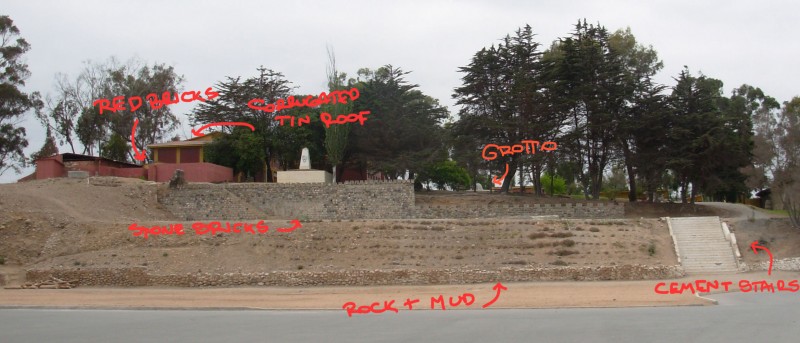

Building the Landscape / Environment

In order to build and model the landscape, Raby uses two softwares: Maya and Unity. His technique involves working with real references as well as objects that are around him. To build the location where the execution take place, he looks at the photographs his dad sent to him from a later trip he took to location of the execution. He also incorporates Google Earth photos and mixes the two in order to get a more accurate modelling of the area.

However, he does not limit himself to these real references. Working also from memory, Raby uses objects that are around him. One thing he remembers is that there were lots of eucalyptus trees in the north of Chile. When he comes to Australia, it is a surprise to find the same eucalyptus trees everywhere and that they are native to Australia. So, he goes to the park two blocks away from where he lives and shoots videos of the eucalyptus trees to model them into Assent. He records the sound of Assent in that park as well.

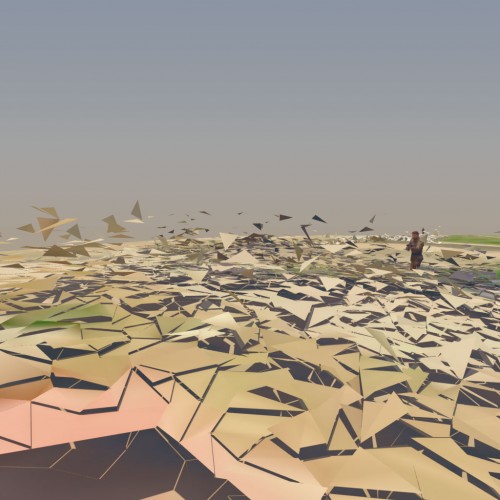

While modeling the whole environment from material gathered from record and memory, he also includes the most basic structural element of 3D modeling, the polygon. Assent is full of visible polygons as a way to foreground the apparatus of the piece. These visual artifacts are included to push the viewer to be conscious of being within the system and to have a conscious outlook on the piece. Instead of tricking the viewer’s perception with photorealism, Raby wants the active participation of the viewer in order to engage with the story.

Mixing real references with objects that are around him while incorporating the visual artifacts of the medium, Raby creates a unique method of approaching design for VR. His method is similar to the way memory itself works, collapsing space and time and making different layers of past coexist with the present as the artifacts and errors of remembering distort them.

Game Mechanics

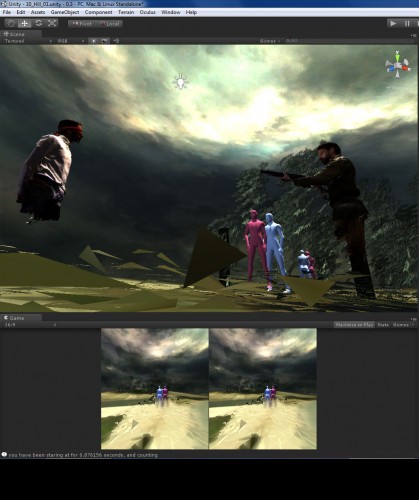

Raby made Assent in Unity, a game-development engine that supports the creation of 3D environments and exports to many platforms. The non-pro version of the engine is also free to download and use, making complex game creation available to smaller studios, artists, and amateurs.

Video games and their ingrained aesthetics are a natural model for other interactive media projects, but Raby struggles with the implications of visual genres like the first-person shooter, where the user is put “in the shoes of the perpetrators”. Inspired by a proof-of-concept video game trailer called “Warco”, (War Correspondent), where the user carries a camera instead of a gun, Raby seeks to find a way to make “looking” rather than acting a central game mechanic. Raby sees this potential in the Oculus, because of the activity made possible through the headset and the way it could focus the physical movement of looking, it seems like a natural way to present the work that would bring in a point-and-click game design, but foregrounded documentary elements. By restricting all interaction to movement by looking, “the game elements are so simple and functional that they are not entertaining.”

Conclusion

Raby uses the physicality of the Oculus and the malleability of the VR environment to rework memory and to provide a new perspective on that day for his father. Muted and contemplative, Assent turns away from the photoreal depiction of violence on modeled bodies found in the aesthetics of triple-A games, to explore how violence can penetrate memory and how it can be passed through generations and relationships.

The strength of Assent lies in its narrative framing of the story, the direct honesty and conscious naivete of its tone, and its creative treatment of the medium, incorporating the artifacts generated by the 3D scanning and modelling process. Although these technologies are not new, they are increasingly accessible to independent artists. Thus, projects like Assent are possible, which push the medium to lengths that are too personal, experimental, and complex to justify the financial risk that such topics could pose to large studios. Assent carves out a space in this new medium for affective storytelling while pushing participants to think about the possibilities of the medium of virtual reality.

0 comments