Sue Ding interviewed the creators of NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism, an ambitious and richly imagined project at this year’s Sundance New Frontier. Artists Carmen Aguilar y Wedge, Ashley Baccus Clark, Nitzan Bartov, and Ece Tankal are part of of Hyphen-Labs, a global team of women of color who are doing pioneering work at the intersection of art, technology, and science. Together they draw on a formidable range of expertise, including engineering, molecular biology, game design, and architecture.

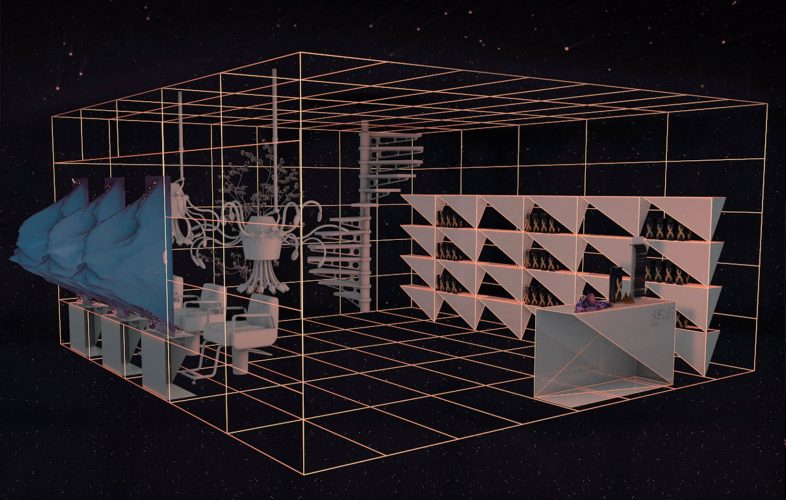

NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism consists of three components. The first is an installation that transports visitors to a futuristic and stylish beauty salon. Speculative products designed for women of color are displayed around the space. They include sunscreen for dark skin, a scarf whose pattern overwhelms facial recognition software, earrings that can record video and audio in hostile situations, and a reflective visor that lets wearers see out while hiding their faces.

The second part of the project is a VR experience that takes place at a “neurocosmetology lab” in the future. Participants see themselves in the mirror as a young black girl, as the lab owner explains that they are about to receive Octavia Electrodes—cutting edge technology involving both hair extensions and brain-stimulating electrical currents. In the VR narrative, the electrodes then prompt a hallucination that carries viewers through a psychedelic Afrofuturist space landscape.

The final component of the project is Hyphen-Labs’ ongoing research about how VR can affect viewers, potentially reducing bias and fear by immersing participants in positive, engaging portrayals of black women. The team would eventually like to use functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) technology to study how participants respond to the experience.

SUE: As a collective, what is your collaboration process like?

Ashley: This is actually the first project we have all worked on together. Carmen and I have known each other for thirteen years. We have always wanted to collaborate on something together, and we were living together in New York this summer and this came about organically. It was a really stressful summer in terms of race relations, political relations, just everything, and I think sometimes when you have that kind of tension it is conducive to creative work and creative problem solving.

CARMEN: We had a really short amount of time so for our products, we came up with the concepts ourselves and then collaborated with designers and developers who have similar aesthetics and ideas. For our visor we collaborated with AB Screenwear, for our earrings we worked with Michelle Cortese, and then for our scarf we worked with Adam Harvey.

ASHLEY: Just as far as us, we all wore a bunch of different hats. We gave each other feedback on the pieces that we each sort of owned, but there was a lot of cross-pollination of ideas and skillsets. We all had to learn stuff that we didn’t know how to do, very quickly.

CARMEN: There was never a decision that was made without consulting the rest of us, and for the most part it was a seamless process. It was nice because it wasn’t very iterative. It was like one shot because we had so little time.

ASHLEY: And then Nitzan is like our VR guru so when we actually started building out the VR, she and Ece really took the lead on that and made something powerful.

SUE: Why did you decide to create part of the installation in VR, and what were the challenges in developing that part of the project?

Ashley: I had been thinking about VR from a research perspective, thinking about the future direction of the medium and wanting to experiment. When I first started thinking about VR it was before Oculus was available, so I didn’t really know where to get a headset or how to even begin. Then after Carmen and I met Nitzan in New York, it all happened organically.

CARMEN: I was looking at VR from the experience side because I really want to augment our human experience, and it was the right way and the right opportunity to make something that I wanted to see, because in so many other industries it’s very difficult to create new content that can be distributed and be seen by a lot of people. I really like emerging technology, because for me at least, emerging technology is the space that is still unknown. There isn’t a hierarchy that we need to try to break into in order to have a voice. We can actually do something, because who’s going to stop us?

NITZAN: Carmen and Ashley would have these amazing visions of what they wanted to see and I would be like, “Okay, we can’t do that, but we could do something else.” That was part of the process of envisioning what this thing should feel like.

CARMEN: We had limited resources. We can do all the things that we want to do, but we didn’t have time, we didn’t have money, we didn’t have people.

NITZAN: Oculus hadn’t launched their controllers at the time so if we started the project today, maybe some stuff would be different. The technology changes so fast.

SUE: I really enjoyed the worldbuilding aspect of this project. There was so much detail and backstory that informed the experience. Was worldbuilding something you conscientiously thought about in developing this piece or did it happen more organically?

CARMEN: We all love science fiction, and we all love thinking about the future. But we didn’t start with like, “We need to build a world.” We came up with these characters, and that’s how we started to build the foundation for this multilayered new universe that we want to populate with women of color who are multidimensional, and really can push a positive and empowering narrative.

Nitzan: We kind of fell in love with the characters as we were creating this, and fell in love with the world. It became its own thing. It’s not the first thing we thought about, but we were using the term worldbuilding as we got deeper into the process, and deeper into the characters..

ASHLEY: We also wanted to take a different approach to Afrofuturist narrative, sort of nodding to that, but also not doing what is typically done, where you have these Egyptian relics and metaphors, something that we don’t really have a connection to. For me, I was really interested in creating a new sort of black mythology within that space. It was really interesting to come at it from a global perspective.

SUE: In building your future world, did you draw on specific influences?

ASHLEY: A lot. I got this book from someone that I really look up to called The Shadows Took Shape. It’s an all-encompassing look at Afrofuturist narratives. That was really impactful for me. Also, just the black American lexicon of literature, and sci-fi.

CARMEN: Also, upcoming and emerging artists, especially Afrofuturists. And the way that you can access them and see their work is through social media channels, so we compiled with our Slack and our Instagram and our Tumblr, and we were constantly sharing new links. There were a ton of women that we looked up to.

ECE: I think it’s a very powerful tool, social media, because we could connect with all of them. Whenever we reached out, they would come and talk to us, and they were very helpful and really excited.

ASHLEY: We were also able to connect with a lot of scientists, which is really interesting for me because this isn’t a typical research project. It’s very heavily aesthetic, and I think that for a long time the divide between art and science has gotten a lot wider, and that’s a gap that we’re trying to bridge.

SUE: What’s next in terms of the research component of the project?

ASHLEY: In terms of the research, this is just a pilot. We’re still coming up with the parameters for what we’re actually looking for, and seeing how we can make our results statistically significant. We don’t want to do all of this work, and then not be able to publish our results, or not have them be reproducible. We’re interested in seeing if, through increased exposure, we can decrease prejudice and bias. We’re working with a team of really talented scientists at Intel and a couple different universities, and we want to be able to tie this research in with every festival that we go to, and take it into the community, and really be able to take science outside of academia and into public spaces. We really want to go to schools and public institutions, because this is why we’re creating this. It’s to encourage a younger demographic who might not necessarily know that these fields are something that they can aspire to create and see themselves in. We want to give them visibility.

SUE: Women of color are underrepresented in the fields of technology and design, as well as in VR content and production. Can you talk about how your work engages with that?

NITZAN: I think our approach started from designing products that think about black women first.

Ashley: Yeah, instead of having to modify products to fit our experiences or not being able to use them, to come at this from the perspective of a product designer, and really design with our needs and our narratives at the center. Now, more companies are starting to do that, but we’re still playing catch up.

CARMEN: It’s just barren, the landscape, and what is being offered to black women. They’re not considered in design, yet they are contributors to emerging technology and design. And so when we started looking at the VR landscape, “Where are the women of color? Where are the black girls?”

ASHLEY: But it’s always a question of like, “Why black women?” Or, “How am I supposed to engage with this work?” There’s so much work that’s only about white men or white women. And no one’s asking that question of, “How do I see myself in that narrative?” My entire life, I’ve grown up watching that and knowing about that history. So we’re giving you an unadulterated view of what it’s like to go into the beauty salon, into this beauty ritual. I don’t really like the word empathy, but it can give you a sense of just paying respect to a culture.

SUE: Can you talk more about that? Why don’t you like the word empathy? Is there another word you would use to describe the affective experience you’re most interested in?

ASHLEY: The reason I don’t like the term empathy, just speaking from the perspective of works like this that take a stance of social justice, it kind of puts the viewer at a higher advantage than the content or than the people who are trying to tell you the story. I don’t really feel like I want anyone to be empathetic towards me or my experience. This is just about telling you a story, it’s not about—

ECE: Making you feel sad about us.

ASHLEY: Yeah, that’s not it at all. I think it’s like mindfulness. We have your undivided attention and we’re going to tell you a story.

All images courtesy Hyphen-Labs.

0 comments