by Sara Rafsky

Upon entering the bustling Plaza Botero in downtown Medellín, the user is surrounded by the cacophonous sounds of the distinctly Colombian urban landscape: snippets of overheard conservations in Spanish float by as the continuous melodic chants of street vendors advertising their wares seem to envelop the space. From there the user continues to stroll, or rather click, through the plaza, passing the corpulent sculptures by the famed Colombian artist, Fernando Botero, for whom the plaza is named. In the corner of the screen appears a woman in white waving energetically. She is “La Jale,” the vivacious source of the cheerful tunes selling local gelatin sweets, and with a click of the mouse, the user activates three short documentary films in which La Jale narrates her 18 years of experience as a street vendor, as well as the hardships she has faced.

Image from Criers of Medellin/ courtesy of pregonerosdemedellin.com

Image from Criers of Medellin/ courtesy of pregonerosdemedellin.com

Welcome to the world of “Criers of Medellín” (originally “Progoneros de Medellín” in Spanish) an interactive web documentary created by Colombian documentary photographer Ángela Carabalí and French web software developer Thibault Durand. Carabalí began working on the project five years ago with her brother, who had long been interested in the world of the street vendors, and spent a year photographing and creating sound recordings. After meeting Durand in 2013, they began developing the idea of an interactive project, which they decided early on would be based upon the natural environment of the vendors. “We wanted to be in the streets,” Carabalí said in an interview. She said there wasn’t a specific explanation why the project would take the form of a neighborhood stroll, but that “the idea arose from the same daily reality of the street vendors,” whose livelihoods depend on being constantly on the move. After encountering La Jale, the user can click his or her way through the surrounding neighborhood, eventually finding their way to four other street vendors, each of whom share their stories in three short documentary video clips.

Finding their subjects required crowdsourcing via Facebook and some old-fashioned shoe-leather journalism on the streets of Medellín. Carabalí said they experimented with several media forms, including an app with a collaborative map, a photo exhibition and more traditional documentary filming practices. But throughout this experimentation Carabalí says the intention was the same, “to get closer and go beyond the profession to see the human behind it.” She wanted users to understand the issues of unemployment and informal work that are inherent to a profession that is so ubiquitous in Colombian society that its practitioners can blend into the background of every day life. In the first video, the user encounters the street vendor in the spontaneous street environment in which he or she works. In the second and third videos, the user scratches below the surface to get a window into the challenges the vendors face and are given a glimpse into their home lives.

This motivation was channeled into the design of the interface so that even when focusing on the interactive components the project wouldn’t lose the connection to the “spirit of the city,” Carabalí said. “Our story was the experience,” Durand wrote in a blog post about the project, “and the experience was the story.”

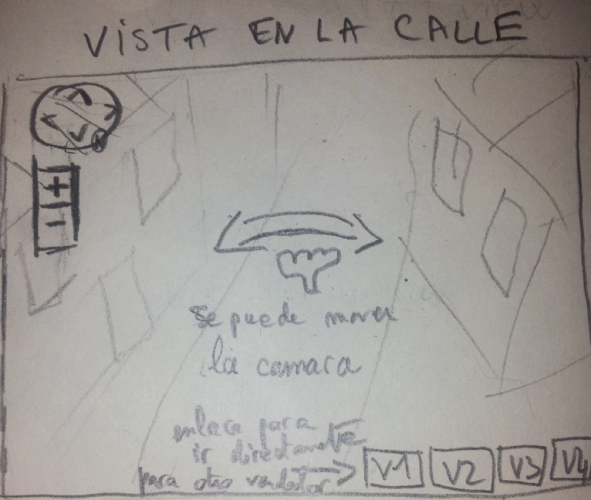

First draft imagining of the street view of “Criers de Medellín”/ courtesy of pregonerosdemedellin.com

First draft imagining of the street view of “Criers de Medellín”/ courtesy of pregonerosdemedellin.com

To create this distinct immersive virtual street walk experience, Durand utilized a combination of such basic tools as GoPro and Javascript. Google Street View did not yet exist in Colombia at the time and limited funding and capacity precluded more complex options like stitching 360 video. So Durand and the team decided to take linear video which, with the help of a tool they found on GitHub called Scroll2Play, the user could control and explore through the act of scrolling.

Once this framework was in place it was time to return the streets of Medellín, where over the course of five days the crew, with GoPros fastened to their helmets, biked repeatedly thorough more than three dozen 100 meter long blocks, making sure to film both sides of the street. For continuity sake, they had to scratch days where the sun wasn’t shining and the installation of the traditional Christmas decorations caused a near disaster for reshoots.

Filming “Criers of Medellín”/ courtesy of pregonerosdemedellin.com

Filming “Criers of Medellín”/ courtesy of pregonerosdemedellin.com

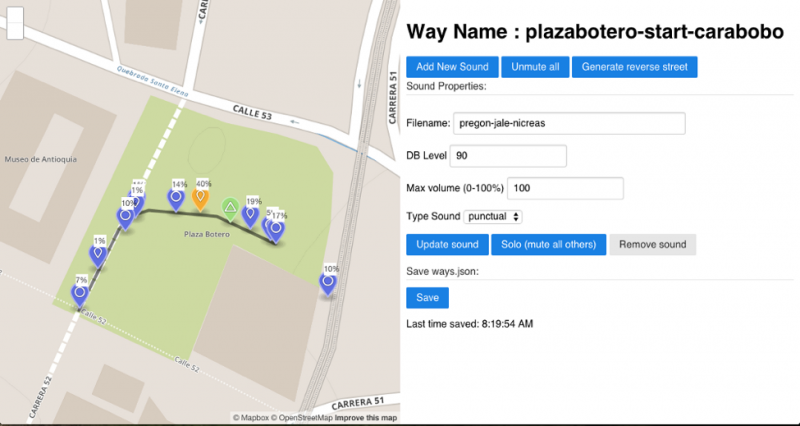

Even more arduous was the simultaneous sound recording, which included a sound engineer recording for up to two hours on each street and resulted in more than three hundred different recordings going into post-production. Durand and his team knew that successfully capturing and then editing these recordings into an immersive and continuous soundscape would be an integral part of the experience. As in real life, “you hear the street vendor before you see her,” Durand said in an interview, “we wanted to replicate that.” A sound engineer from Medellín, operating alongside the filming, recorded both ambient sound from the streets that fades in and out as the user advances in the finished experience, as well as more detailed punctual sound like the cries of the individual vendors.

With an interface they built on top of the web documentary, Durand and his team mapped out the project using GPS coordinates to geo-spatialize the sounds and compute the distance between site of the recording and the position of the user.

Sound editing “Criers of Medellín”/ courtesy of pregonerosdemedellin.com

Sound editing “Criers of Medellín”/ courtesy of pregonerosdemedellin.com

After a lot of design and user experience iteration, Carabalí and Durand launched “Criers of Medellín” in 2015 but they hope the project will have continued relevance in the future, perhaps if even only as an archival document of a Medellín that may no longer exist. “In 50 years maybe there will be no more street sellers,” Durand said. “It will be a good document to have. Maybe we can do a project comparing the urban landscape 50 years from now.” After a pause he addressed Carabalí, “I think I just got an idea for a future project.”

0 comments