by Sue Ding

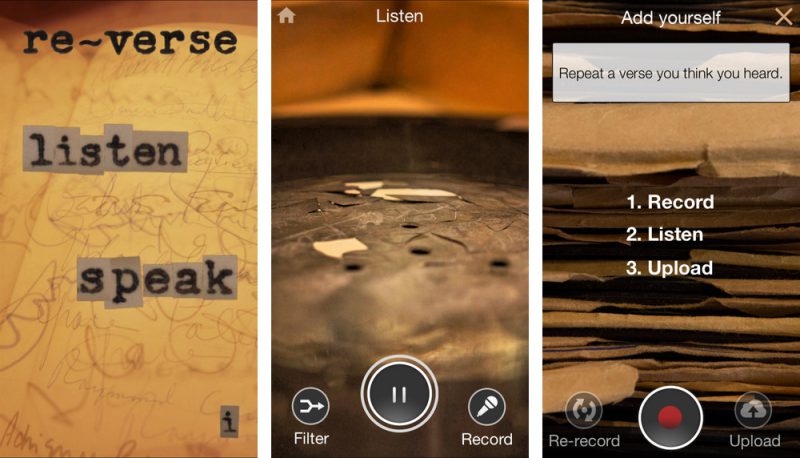

On a damp January day, I stand in front of one of Harvard Yard’s ornate wrought-iron gates. In the yard, snowdrifts are beginning to melt around the pathways, creating treacherous puddles of slush. Students and professors in peacoats and fleece jackets—and in one case, basketball shorts—stride purposefully between stately brick buildings. A large tour group, an omnipresent sight here, moves at a more leisurely pace. I take out my iPhone, put on my headphones, and open up the app that I’ve downloaded for this occasion. The start screen only has two buttons: “listen” and “speak.” I press “listen,” and begin to meander across the yard.

Slow, atmospheric music immediately begins to play. The soothing tones create a slight sense of distance—I feel like I have entered a separate, parallel Harvard Yard, a space of whispered intimacy at a remove from the bustle of campus life. As I pass an intersection, a man’s voice begins to speak in my ears. “I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox,” reads William Carlos Williams from his famous poem “This Is Just To Say.” His words drift off as I walk forward. A few moments later, I hear a man pensively speaking, as if to himself, in Arabic. After wandering for some time, I pause to explore the “speak” option, which invites me to record my own voice to add to this unruly collection and provides some prompts, like “Read some verses,” “Talk about a nearby gate,” and “Ask a question based on something you heard.” Back in “listen” mode, I find that I can also filter what I hear, based on these same prompts. Voices run together, overlapping, scattering, sometimes harmonizing serendipitously with the omnipresent music. The sensation of the soundscape responding to my bodily movement is an interesting one; I experiment a bit, pacing back and forth and feeling a bit self-conscious as I lean first one way and then the other. The responsiveness, minimal interface, and seamlessly blended sound combine to create a profoundly embodied and immersive experience.

This is re~verse, a participatory, location-based installation by sound artist Halsey Burgund, based on his platform Roundware. Created in collaboration with Harvard’s metaLAB and Woodberry Poetry Room, it features more than a thousand audio clips from Harvard’s collection of recorded poetry. This rich archive spans nearly a century and includes the first recordings of T.S. Eliot and Sylvia Plath, as well as readings by luminaries such as W. H. Auden, Anaïs Nin, Amiri Baraka, Ezra Pound, and Audre Lorde. re~verse brings these recordings out into the physical space of the campus, and invites students, poetry lovers, and passers-by to participate in an embodied exploration of poetry, space, and history, as well as to contribute their own voices to a murmuring, intricate, and constantly evolving tapestry.

Click here to listen to an audio clip from re~verse:

Contributory, Location-Based Audio

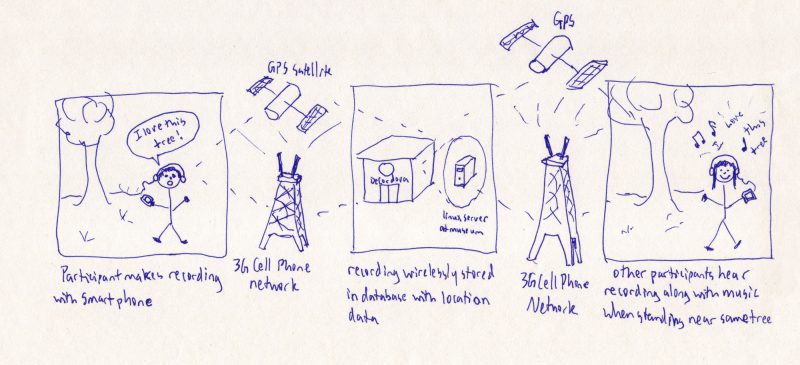

Developed by Burgund to facilitate his sound installations, Roundware is a contributory audio platform that allows creators to augment the physical landscape with location-aware layers of music and recorded voices. Using a mobile app and headphones, participants are immersed in a soundscape that responds dynamically to their location and movement. They can listen and wander, filter their audio stream in a number of ways, or record their own commentary to add to the project. Contributions are tagged with location information as well as project-specific metadata—for example, in re~verse, participants can self-identify as poetry lovers or neophytes. Gradually, user contributions build up across the landscape, documenting a multiplicity of voices and subjective experiences over time.

Burgund has used Roundware to create installations across the globe, from a cranberry bog in Massachusetts to World War I sites in northeast England to downtown Christchurch, New Zealand. He has also developed Roundware-based educational audio projects for the Smithsonian, UNESCO, and other cultural institutions, including projects focused on accessibility for the blind. The works range in their thematic focus, sometimes simply inviting participants to share a thought or experience, sometimes emphasizing topics like political discourse, local history, or poetry, as in re~verse. And while Roundware’s functionality supports the creation of contributory, location-based experiences, Burgund has also used it for browser-based audio projects and site-specific sound installations that are neither contributory nor location-aware. The platform lends itself to a host of different applications, and because it is open-source, even Burgund himself isn’t privy to all the different instances and modes in which it has been employed.

Project Genesis

Roundware began in 2007, as technical platform for Burgund’s ROUND installation at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum. As a sound artist, Burgund has long been drawn to the human voice—its musical qualities, shades of emotion, and intimate reflection of the diversity of human experience. For ROUND, Burgund developed a tablet-based system (smart phones had not yet become mainstream, although they were poised to do so later that year) that invited museum visitors to contribute their thoughts about various works of art. While standing in front of a painting, viewers could listen to commentary by a curator, hear observations from previous visitors, and add their own opinions. “It all came out of my dislike of museum audio tours,” says Burgund. He wanted to democratize conversations about art, and disapproved of authoritative audio tours telling visitors what they were “supposed” to think.

The first Roundware interface, for Burgund’s Round installation at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

This emphasis on openness and plurality is embedded deeply in the platform itself. Roundware’s website emphatically states, “Roundware is not audio tour software! In some ways, Roundware is the anti-audio tour platform.” It further explains the distinction:

- Audio tours are traditionally about a single authoritative voice whereas Roundware is about a multitude of voices, opinions and ideas mixed together.

- Audio tours tend to be linear experiences; Roundware is based on a non-linear, flexible, participant-driven, immersive experience.

- Roundware is designed for sculpting an aesthetic experience, not for explicitly delivering educational or interpretive information.

ROUND established both the platform’s core functionality—the ability to record audio, add recordings to a database, and play them back in a stream with specific parameters—and its core affordance, building contributory, location-based installations. Since 2007, Burgund has continued to develop Roundware in a heavily iterative process, regularly expanding its functionality in order to fulfill his own creative needs as well as specific requests from clients.

Functionality and User Experience

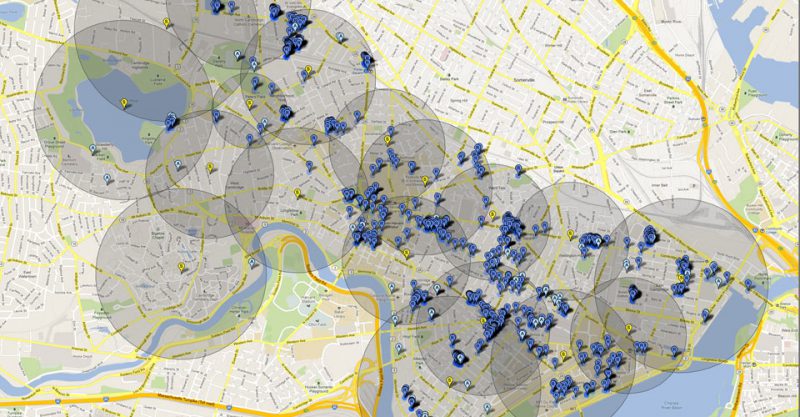

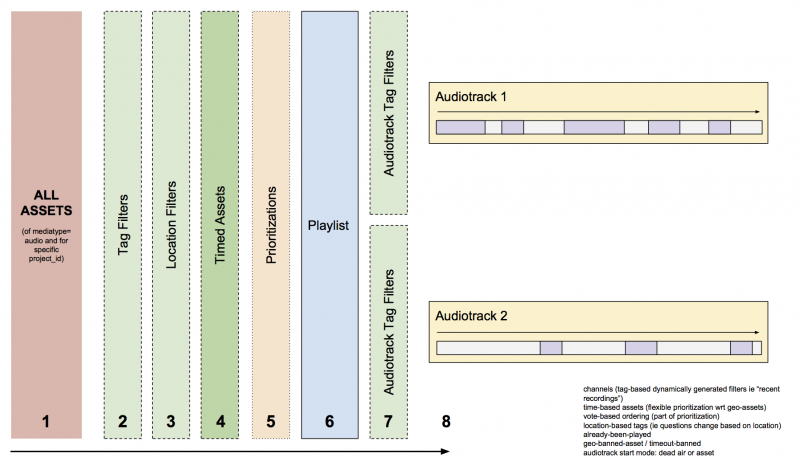

Roundware is a client-server system; clients for iOS, Android, and HTML5 browsers communicate with the Roundware server, which runs on Django, Apache, and Ubuntu Linux. Within this system, two basic categories of audio content are supported. A base layer of continuous audio, comprised of site-specific music composed by Burgund, is placed over the entire area of the project. Different tracks are each assigned to a relatively large geographic area—essentially, a polygon that he draws on a map. As a participant moves across these invisible shapes, they will hear their corresponding musical pieces, which collectively form the overall composition. The second layer of sound, the momentary layer, consists of intermittent audio clips—typically in Burgund’s work, these are voices, although any kind of audio can be used—that are shorter, non-looping, and assigned to a smaller area. Burgund adds some of this momentary audio to the initial soundscape, and over the course of the project, participants contribute additional snippets using the mobile app. As listeners wander around the project area, their physical location, as well as any filters they have selected, triggers nearby audio clips that play for a brief moment. It’s possible to simply have a silent base layer, but Halsey sees the music as an essential component of creating an overall environment, an ambience within which all the content lives. He says, “I think of the continuous layer as the ocean that the intermittent audio is swimming in.”

Beyond this basic two-layer structure, each installation is also shaped by an array of aesthetic and experiential considerations. For the momentary audio, each clip has a circular area of distribution, with a center point and a radius. Creators can control the size of the radius—for example, choosing a larger radius for larger geographic areas, so that participants are more likely to trigger the files. Once someone triggers a clip, it plays for a predetermined length of time, even if the user moves outside the file’s radius. This is an important part of the experience design: if clips stopped playing as soon as users exited their radius, the experience would largely consist of two- or three-second clips, which would be unsatisfying and would not allow users to substantively engage with the content. How long the clips play once participants move outside their radius can be tailored to the needs of specific projects. An algorithm also ensures that visitors don’t hear the same clips repeated during their experience. Burgund makes the case that these details are crucial to both Roundware and the type of work that it supports:

Roundware has a whole lot of parameters that would not be there if somebody designed it for advertising. I think that its artistic roots are very clear in that sense. […] This is all the aesthetic stuff. This is how long the recordings are, or how long this dead space air is between. This is how it fades out. This is how it pans back and forth. Those things are really important.

This careful attention to participatory aesthetics is crucial to the success of both participatory documentary and location-based works.

While Roundware provides creators with a great deal of specificity, projects created on the platform also inherently include elements of chance and randomization. Participants walking the same route in an installation will not hear precisely the same things; Burgund says, “It would be almost impossible to recreate the exact same experience.” In each installation there are areas of high density, where many audio clips have been added—perhaps near a bench where people can pause for a moment, or a landmark that invites exploration. In these areas, creators can limit how many files will play at once—Burgund usually limits it to two at a time—so that the overlaid clips do not simply become incomprehensible noise. Within that restriction, the length of each clip is different, and the ordering of the clips is randomized. Moreover, there are what Burgund calls “systemic randomizations,” small variations due to GPS’s imperfect accuracy, or the fluctuating strength of a wi-fi signal. And of course, most visitors’ paths will be unique in some way: how fast they walk, where they decide to pause, whether they choose to retrace their steps. Thus, Roundware offers an experience that is at all times a dialogue between creators, participants, and the dynamic conditions of the physical and virtual environment around them.

Contributory Ethos and Collective Storytelling

Roundware was conceived from the very beginning as a contributory platform—the capacity for users to add their own content was central to its functionality and ethos from the start. Burgund stresses the distinction between contributory and interactive projects: regarding the latter, he feels they often seek solely to create an ephemeral individual experience, one whose novelty fades quickly away and which has no effect on other participants. In contrast, in a contributory project, “You’re contributing to a larger whole, leaving something of yourself for others, co-creating something such that future participants are affected by past contributions.” (He finds “participatory” to be a more nebulous umbrella term, used to describe both interactive and contributory works.) Roundware contributions are uploaded automatically and immediately added to the piece, with no approval period. Burgund believes this is crucial to encouraging constructive and thoughtful discourse, saying:

If you tell your participants you don’t trust them, then they’re going to do stupid things. If you tell them you trust them, you give them good examples, you encourage them in the right way, then generally they’ll do something that’s respectful and consistent with the ethos of the piece.

He does listen to the recordings after they have been uploaded, primarily because he is interested in hearing what people have contributed. Out of thousands of contributions, he says he has only had to remove offensive content—what he describes as hate speech—once or twice. The only other oversight he exercises is modulating the volume of loud screams so that they do not cause physical discomfort to listeners. This openness and immediacy produces an environment that encourages participants to playfully experiment with creative modes of collective storytelling.

One day in 2010, Burgund checked on the new additions to his Scapes installation at the deCordova Sculpture Park. A teenager had recorded a frantic, whispered message: “I’m behind this sculpture. I’m trying to hide from these zombies that are walking around. Wish me luck.” Amused, he thought nothing more of it. Then, a few days later, a new recording showed up in the same area of the park: “I was just by that rock over there, and there was a dead body and a zombie was eating its brains.” From there, the story continued to unfold over the next four months, with the beleaguered survivors finally being airlifted out by helicopter.

Beyond its creativity and the entertaining arc of its narrative, what was extraordinary about this zombie epic was the fact that so many different people—most of them children—had contributed to this story, all visiting the installation independently at different times. With no prompting beyond hearing a snippet of the story during their visit to the park, they enthusiastically joined in this collective storytelling effort. Roundware’s dynamic soundscapes augment the physical landscape with a new layer of collaborative creativity and social interaction; Burgund also points to other examples in which people left spatially oriented instructions for future visitors, creating treasure hunt-like experiences.

Watch a short video about Scapes:

Authorship and User Agency

Burgund conceptualizes his authorship in these works as “framework building […] I create this framework, which is technical and conceptual and aesthetic, and then I just open it up for people to come in.” He views his work as a collaboration between the participants and himself, and enjoys that the results are not fully under his control: between the algorithmic randomization of Roundware and the systems supporting it, the ever-changing conditions of the physical space of the work, and the diverse ways in which participants engage with and contribute to the experience, the results of this collaboration often surprise Burgund and inspire new directions for artistic and technological exploration.

At the same time, he shapes users’ experiences and contributions, “nudging” them to participate in the piece, via his decisions about spatial layout and user interface. And while users certainly play an essential role in each project, authoring much of the content, their agency is ultimately quite restricted. For example, they do not have the ability to select a particular item and play it when they want to hear it, and the user interface provides no information about what content is located where. Both artist and participants must accept a lack of total control over the experience. Burgund says that the limited user agency is on purpose: “I don’t want people to have to make a decision that they’re not equipped to make.” He feels that viewers, when presented with a selection of media content without much context, often choose arbitrarily. By taking this choice away, he hopes to simplify the user experience as well as counter subconscious biases and behavioral patterns.

Burgund uses the open-source software term BDFL, or “Benevolent Dictator for Life,” to describe his role managing the Roundware code: while it is open-source, he decides what is ultimately added to the core code, guides its overall development, and enforces aesthetic standards. Arguably, BDFL also applies to Burgund’s stewardship of the overall Roundware experience. Although Roundware installations are collectively created via user contributions, Burgund remains the singular artist gathering and shaping these inputs into a work that represents his artistic vision.

Non-linear Exploration

In contrast to linear spatial narratives that physically and figuratively bring participants from one point to another, like audio tours with a set of specific stops (often linearly arranged), Burgund says, “Roundware is just an area that’s been activated, where you’re tuning in to this evolving audio stream. It’s like a radio.” There is no explicit narrative structure that guides viewers from place to place.1 Their path is determined by their own whims and curiosity, as well as each space’s unique and dynamic characteristics—from landmarks to weather to the flow of people through a location.

This nonlinear mode of exploration evokes the dérive (taken literally, “drift” or “drifting”), a concept formulated by French theorist Guy Debord. Debord was a founding member of the Situationists, an avant-garde collective of activist artists who envisioned subversively playful practices to counter the alienation, rationalization, and predictable hierarchy of modern cities. Debord described the dérive thusly:

[…] a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiences. Dérives involve playful-constructive behavior and awareness of psychogeographical effects, and are thus quite different from the classic notions of journey or stroll. In a dérive one or more persons during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there.2

The notions of fluid movement, immersion in ambience, and attentive participation in an environment are all reflected in the Roundware experience. Each installation’s multiplicity of voices, running together and speaking over each other, also resonates with the Situationist project of destabilizing singular, authoritative narratives of public space.

Layers and Temporality

Beyond the digital layering of the voices themselves, Roundware also exists as an invisible virtual layer on top of a physical place, inviting participants to consider a pluralized sense of place and the complex relationships between location, the physical, and the virtual. Each installation itself is composed of a multitude of temporal layers. Often, the initial content is already temporally layered—as with projects like re~verse in which Burgund juxtaposes historical recordings from different periods with contemporary music. Regardless, over time, all Roundware experiences build up intricate layers of media content, as participants add to each installation throughout the duration of its existence. These recordings remain tethered to the specific spot in which they were made, so participants in any one location encounter a dynamic mixture of all of the thoughts and experiences that previous visitors shared at that spot. The often densely layered fragments, sometimes spanning centuries, become compressed into the present experience of each participant.

At the same time, user recordings join a documentary archive, but one with almost no curation, moderation, or requirements for inclusion. Rather than looking backward to collect documents of importance, Roundware creates an archive of the present that is both virtual and, through its geolocation, profoundly physical. In doing so, it offers a conception of space as a temporal process, and asks participants to reexamine commonly held notions of history, memory, and documentation.

Archaeologist Michael Shanks’ writing on the deep map (a term coined by William Least Heat-Moon in his 1991 book PrairyErth) is helpful in understanding the ways in which past, present, and future spatialities can intersect:

[…] The deep map attempts to record and represent the grain and patina of place through juxtapositions and interpenetrations of the historical and the contemporary, the political and the poetic, the discursive and the sensual, the conflation of oral testimony, anthology, memoir, biography, natural history and everything you might ever want to say about a place.3

Deep mapping counters simplistic binaries between past and present, public and private, objective and subjective. It defamiliarizes our everyday surroundings in order to highlight overlooked features and interconnections, reflecting “the palimpsest that is landscape – the percolating time that folds together the many fragmentary traces of pasts present in any one place.”4

Audio Augmented Reality

Burgund conceptualizes Roundware as audio augmented reality: “I’ve always thought of it that way. It augments the physical landscape with a layer of audio. But I’ve only recently taken to describing it that way, because people now know a little more about what that is.” Audio AR is inherently location-based, with audio files triggered based on a user’s location. It is already being used for a plethora of applications, including gaming, immersive theater, navigation, tourism, and accessibility for the visually impaired. However, mainstream industry discourse around AR remains overwhelmingly focused on head-mounted displays.

Audio AR’s lack of visibility (pardon the pun) is partially due to the same terminological confusion that plagues both location-based media and augmented reality. The concept of audio that augments the physical world through location-based content has been variously described as dynamic spatial audio, ambient spatial audio, location-based audio, location-aware audio, and geotagged audio, among other terms. Despite this lexical difficulty, audio AR has unique affordances that underscore some of the limitations of visual AR.

Burgund argues that visual AR puts a camera between users and the world, “reducing the world to the part that fits into the margins of your screen.” By pulling users’ attention to a screen rather than the world around them, visual AR often prioritizes the augmentation itself, rather than the reality it augments. Many AR demos, for example, emphasize a scientific model or whimsical character, rather than the space users are in, or their interactions with surrounding people. A key affordance of both location-based media and AR is that they are able to build on, and interact with, the most engaging characteristics of the physical environment they are situated in: from historical details to natural scenery to electronic displays. This potential risks being diminished in camera- and headset-mediated experiences. Burgund says, “I think it is crucial for the people designing these systems to think about this and do what they can to really augment rather than mask reality.”

Roundware also invites reflection on embodied interaction and user interface in AR. Roundware installations require relatively little interaction via the mobile app, with the exception of recording audio contributions. For the most part, bodily movement is the primary user interface. “My motto has always been, ‘Press play and put it in your pocket.’ Then you’re just walking,” says Burgund. For AR, it is neither feasible nor desirable to have bulky, elaborate interfaces—in terms of both simplifying user experience and not distracting users from the environment around them. Most manufacturers of head-mounted displays are already working with gestural interfaces, in which users interact with computing systems through hand motions (or other bodily motions). Ideally, this creates a more intuitive and immersive experience by seamlessly linking digital devices with the physical world. Rus Gant, Director of Harvard’s Visualization Research and Teaching Laboratory, notes that audio AR represents an underexplored but crucial aspect of conceptualizing how AR can and will function on a material level. Speaking about Apple’s new Bluetooth earbuds, he says:

[People] think they’re just headphones. No, this is much more specific. This knows where your head is looking, knows where your head is in geographic space. The headphone knows that. It can check with the phone: ‘Where are we? Now we’re over here.’ And then it can check with the cloud: ‘Did we do this last week at the same time and the same place?’

Gant argues that these earbuds, in combination with a smartphone and other linked devices like smart watches (and eventually, head-mounted displays), constitute a “body-centric ecosystem” that will redefine approaches to AR.

Access and Activism in Roundware’s Future

Roundware was designed with access as a key principle. Burgund is passionate about creating art outside of traditional white cube art spaces: as an artist, he draws on the inspiration of being in everyday spaces where people live, work, and play. He also wants his work to be accessible to a broader, more diverse audience, rather than “behind the gates of some art museum where there’s either a pay wall, or a class wall, or a socioeconomic wall, purposeful or not.” Roundware is also open source, for two primary reasons. Firstly, Roundware depends on open source software to operate (including Apache, Ubuntu, and Django), so Burgund feels it is important to give back to the community. Secondly and perhaps most importantly, he says:

The whole philosophy behind Roundware of collectively creating something greater than any single contributor over time, piece by piece, is shared with the open source, social coding community. It feels wrong to have a platform that enables work that depends on community contributions be itself closed off and proprietary.

Although Roundware is open source, Burgund acknowledges that it would be difficult for someone without prior programming experience to set up their own installation. And of course, most of his projects require a mobile phone, another barrier to entry. One of his main goals for the platform going forward is to make it more user-friendly and accessible—this includes bringing Roundware into schools as a learning tool, as well as developing better methods for publicizing installations that are otherwise invisible.

One of Roundware’s most intriguing potential applications is for activist-oriented projects. The platform’s onsite documentation and archival capabilities could serve as important tools for activist movements, which are often oriented around specific events and locations. In 2015, Burgund and Egyptian-Lebanese artist Lara Baladi created the Roundware installation Invisible Monument, located in Boston’s Dewey Square—the main site of Occupy Boston. Although onsite documentation wasn’t possible in this case (the protests took place in fall 2011), Baladi and Burgund gathered recordings made during that time period, and used them to recreate a soundscape of the protest. In the future, demonstrations and other events could be both recorded and preserved on-site, creating a ground-level archive of participants’ experiences. This possibility suggests important questions about physical and virtual public space: when protests are shut down and activists are forcibly removed from parks and streets, what does it mean that a virtual record of the protesters could live on in that same space? By geolocating digital media, how can location-based projects intervene in our understanding of free speech and public space? Burgund points out that, since Roundware requires no hardware onsite, “I can do a Roundware installation without any permission. I could put a Roundware installation inside of the Pentagon and nobody would listen to it, but it would be there.”

Conclusion

Roundware is already an incredibly versatile and conceptually rich platform: an artistic and documentary tool for realizing site-specific soundscapes; an asynchronous, location-based social network for collective storytelling; a narrative platform supporting experimentation with linearity and temporality; and an example of audio AR that invites us to re-think AR content and user interfaces. Users are immersed in enchanted landscapes that invite spontaneous interactions, playful discovery, and creative contribution. Roundware’s adaptability for civic interventions, and the potential for it to be more widely accessible for both participation and creation, are only two of many exciting avenues for future technological and artistic experimentation.

Notes:

1. Recently, Burgund introduced the capacity to add time-based assets to Roundware installations; this new feature introduces the possibility of introducing a structured narrative arc into the experience.

2. Guy Debord, “Theory of the Dérive,” in Situationist International Anthology, ed. and trans. Ken Knabb (Berkeley, CA: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), 62.

3. Michael Shanks and Mike Pearson, Theatre/Archaeology (New York: Routledge, 2001): 64-65.

4. Jeffrey Schnapp, Michael Shanks, and Matthew Tiews, “Archaeology, Modernism, Modernity,” Modernism/Modernity vol. 11, no. 1 (2004): 11.

Additional References:

Halsey Burgund, interviewed by author, 2016-2017.

Rus Gant, interviewed by author, 2017.

0 comments